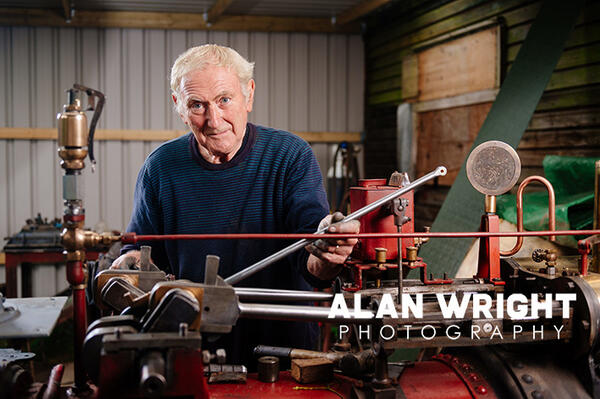

ENGINEER MICHAEL LUGG

Published on 1st September 2021

I was born in 1945 and lived at Gore Farm at East Street, Billingshurst. During the war, a German bomber dropped bombs behind the village. One landed close to the workshop and broke the chimney on one of our traction engines. Another 200 yards and it would have taken out the farmhouse!

My grandfather, James Oppy Lugg, had moved here from Cornwall in 1900. He was an apprentice at Carter Bros in Newpound, where he worked until about 1925 before starting his own business at Gore Farm. My father, Gordon Lugg, took over when he died. That’s where I grew up.

I was in the first intake of pupils at Weald School in 1956, which has grown beyond recognition since then. It had a metal workshop and I was interested in that, as well as technical drawing. I was the first boy there to get the cane, which is a record nobody can take away from me! V.V. Gee was the Headmaster then and he could be very strict.

At Gore Farm, we specialised in restoring steam engines and industrial boilers. During the war, a lot of engines were cut up for scrap, but fortunately in the 1950s a few preservationists realised they were disappearing and tried to save any that were left. Sometimes, we would have more than a dozen steam engines in the yard. We fixed a lot of factory and hospital boilers too, which was big business in those days, as we covered the whole of the south east and south London too. But industrial boiler work was hard and my interest was in steam engines.

At that time, Penfold’s had an engineering yard near Arundel. They were diversifying the business by becoming John Deere agents, and Penfold’s contracting work was coming to an end. So, a collector from Hampshire bought some old steam engines from Penfold’s, including a 1910 Burrell traction engine, which came to our yard for repairs.

After school, I would spend ages polishing it and making it look good. This collector came back with the logbook and said, “You've done such a good job looking after that, I think you’d better keep it!” There’s a British Pathé video online of me driving it with two friends when I was 11-years-old.

I finished school and joined Blaker’s, a welding business in Dial Post. I had been doing repairs on boilers and Jim Agate, the foreman at Blaker’s, noted my interest in engineering, so they were happy to take me on as an apprentice. I was there for five years and spent two evenings a week at Crawley Tech, gaining a City & Guilds qualification in welding.

After serving my apprenticeship, I went to work with my father at Gore Farm. But it was mostly industrial boiler work and didn’t give me much satisfaction. So, I started my own business on The Haven, focusing on steam engine restoration. What I love about engines is that they look fantastic. Every pillar and column was designed not just to be functional, but pleasing on the eye. Perhaps it’s that quality that saved many of the engines in the end. They are like antiques, and people will always appreciate things that are well made.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s there was a lot of work coming in, as the original boilers on steam engines were at the end of their working life and needed rebuilding. Now, some are on their second preserved engines. We also restored steamboat engines too, which are just as beautiful.

Because of their rarity, the cost of steam engines has gone through the roof. I know from the logbook that my first engine cost its owner £80, but even Showman engines (used at the circus or funfair) used to sell for £50. Often, they would remove the Dyno off the front and put it on to a diesel lorry, then sell the engine for next to nothing. Now, a Scenic Showman’s engine will sell for about £700,000 because of its history and heritage. They are lovely looking and highly collectable, so if you want to buy one, you’ll need to compete against buyers all over the world.

I remember Mr Penfold coming down to the yard and giving me a set of paraffin lamps to hang off the front of my steam engine. He went into a storage van and it was full of lamps. He said to my dad, “If you want any, you’d best take them now because they’re all going to scrap otherwise.” Now, a set of lamps like that will cost you £1500!

I’ve always loved driving the engines and even when I married Jane, we went to the church on a steam roller. Driving one is a challenge, as you have to generate the power to move. To do that, you have to maintain a steady fire to keep the steam temperature up, keep the water level in the boiler, as well as steering and watching the traffic. You also need to know where to pick up water. In the old days there were a lot more streams around, but now you have to plan your route carefully.

The problem with taking steam engines on the road now is that cars are so fast and drivers don’t work out the speed differential. In a split second, they are right on you, no matter how many flashing lights and slow vehicle signs you might have. There’s always somebody who’s not paying attention. It’s okay to go out on shorter runs on rural roads, but when we travel further afield, it’s best to transport the engines on a low loader.

The first steam rally I remember was in Appleford, Berkshire, in 1952. There was a race - up the field and back again - and the winner received a barrel of beer. It captured people’s imagination and gradually crowds grew at these events. When they saw the engines in action, everyone wanted one, so they were buying them out of scrapyards and trying to preserve them, then taking them out as a hobby. It just becomes a way of life!

Eventually, events like the Dorset Steam Fair became very popular, attracting people from all over the world. But today, great fairs like Rudgwick Steam & Country Show are disappearing because of health and safety regulations. It’s hard for rallies to justify the costs involved. If a health and safety inspector looked inside the cabin of a steam engine, he’d have a heart attack!

It’s a shame we are losing these events as children love seeing steam engines in action. When we use an old engine to power a sawmill, with huge tree trunks sliced to pieces in seconds, it really grabs people's attention, as they’ve never seen anything like it.

There is a lot of interest in steam engines across the world, particularly in Holland, Germany, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and America. We have friends in New Zealand who used to regularly come over for rally season, shipping engines over in containers. They love English pubs more than anything! We have been out there four times too, as we can do longer road runs, as they have much less traffic in New Zealand.

Unfortunately, my wife passed away a year ago, so it’s nice to have this hobby to keep my mind active. I’m still busy and always have one or two projects on the go, and lots of people call for my advice. I still have my own engine, Dauntless, and my daughter owns a green Burrell, called William the Second.

I steer away from heavy boiler work now and focus on the more refined work, as there are places and businesses more geared towards heavier equipment nowadays. There are probably a dozen businesses scattered around the country specialising in restoring steam engines.

There is still a Lugg’s Close in Billingshurst, where my father’s yard used to be, although the landscape is so different now that it’s hard to even imagine how it used to look. My daughter Kate and her husband help me now and I’m hoping my grandson will be interested in keeping these old engines going too. In the same way that heritage steam railways are a tourist attraction, steam engines are also a historic part of the UK’s industrial story and it’s important to keep them going.

WORDS: BEN MORRIS

PHOTOS: ALAN WRIGHT/MICHAEL LUGG

To watch the British Pathé video of Michael online. Search ‘Boy’s Traction Engine 1956' or click here.