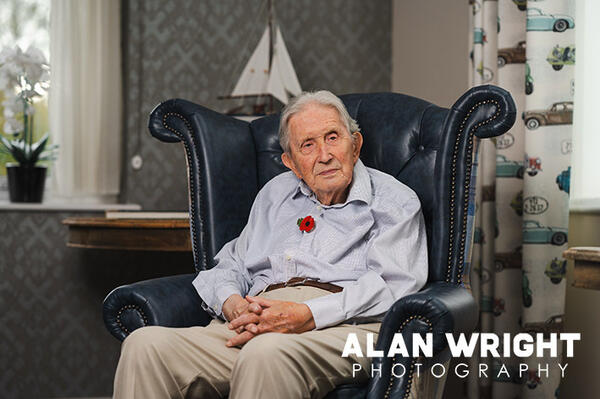

GEOFFREY WEAVING OF HORSHAM

Published 1st December 2024 in AAH Magazine.

Geoffrey Weaving, a resident of Skylark House in Horsham, recently celebrated his 100th birthday and also attended the Remembrance Sunday service in the Carfax. Here, Geoffrey recalls memories of the Second World War, his career in banking, and why he continues to honour the fallen…

I was born in Glasshoughton, Yorkshire and grew up in the village of Brayton, near Selby. I did well at school and particularly enjoyed mathematics and rugby. When I left, I spoke to my father about what I should do for work. He was a skilled joiner and carpenter, but I wanted to pursue a different career. He suggested a bank as they had a good pension schemes, which turned out to be good advice! I found a job at Midland Bank and had been there two years before I signed up to join the Royal Navy, aged 19.

I loved reading and had been fascinated by accounts of the First World War, when they had used morse code to relay intelligence. So, the idea of using my mathematical skills as a Telegraphist appealed. On my first day at training college in Portsmouth, they took away my clothes when they handed me a fresh uniform and kit bag. They posted my clothes home in a bag without a note, so my mother was very worried about what had happened to me until I was able to write home!

During an intense six-week programme, I learned about wireless operations and became proficient in morse code. I then travelled to the Welsh port of Milford Haven and boarded HMS Blizzard, which was tasked with clearing mines the Germans had dropped in the Atlantic, targeting Allied convoys moving between America and Europe. My job was to relay information about the location of enemy ships and mines to provide safe passage for Allied ships. I enjoyed my time at sea, as the camaraderie was good.

Later, I received orders to transfer to HMS Astral and headed to the naval port at Great Yarmouth. HMS Astral was a hydrographic ship used for navigation during the war. We took part in training exercises in the North Sea and people were bringing all kinds of sophisticated equipment on board, so we wondered what was happening. We headed to the Solent and it was clear something significant was being planned, as several hundred ships had gathered there. We were called on deck and told we would be crossing the Channel to support the invasion of France.

HMS Astral was not a battleship and had nothing to fight with. Our role in Operation Overlord was to ensure safe passage to the French coast for a Canadian regiment travelling behind us. Five beaches had been marked out for the D-Day landings: the Americans were to lead the assault on Utah and Omaha beaches, while the British led the invasions at Sword and Gold beaches and the Canadians at Juno beach. Juno was perhaps the most heavily defended of the five beaches and the one HMS Astral was assigned to.

We set off in the evening and arrived very early on the morning of 6 June 1944. We saw the French coast in the distance. The minesweepers led the way looking for mines and our job was to follow on behind them, laying buoys to mark a safe channel for the landing craft to follow. HMS Astral had surveying equipment on board that could map out the seabed and we tried to avoid obstacles, making it easier for the landing craft to reach the beach. We were still laying buoys in the Channel when suddenly the warships behind us started firing at the beaches, aiming for the German defences. The noise was deafening, but we had to carry on doing our job.

The Germans were not firing at our ship, so all I could do was watch the terrible carnage unfold. They fired like mad when the ramps came down and the Allied troops started running out on to the sand. Some were shot and died in the water, while others were wounded and drowned because of their heavy packs. But eventually our troops moved up the beach and when the firing stopped, gathered with those involved in invasions at the other beaches to form an army to march into France. That day was the start of the turning point of the war, when the momentum shifted from the Germans to the Allies.

After the D-Day landings, HMS Astral assisted with the construction of the Mulberry artificial harbour. Following that, we sailed up the coast of France to the River Scheldt, used as a supply route to Antwerp, Belgium. At the river mouth at Walcheren, the Germans had mounted a determined resistance and our job was to play our part to help secure the important supply route to Antwerp, aiding the Allied advancement towards Germany. After that, we sailed back to Great Yarmouth and after the war ended, conducted exercises in the North Sea.

I was demobbed in June 1946. I didn’t consider a career in the Navy as I enjoyed working at Midland Bank and was keen to get back to it. I was ambitious and took exams to further my career. I was offered the option either of travelling aboard Cunard liners and handling the banking requirements of American businessmen coming to Britain, or moving to a larger branch in Sheffield to broaden my knowledge of banking. I chose Sheffield. My friends couldn’t believe that I had turned down the chance to travel with Cunard. One said, ‘You might have met the daughter of an American billionaire!’

I travelled from Sheffield to my home town of Selby every weekend to see friends and family and to play rugby. One day, I injured my shoulder during a game and had to go to hospital. I went for an X-Ray and it was there that I met a beautiful Irish nurse called Bried. We married in 1955 and bought a house in Sheffield. We moved to York when I was promoted to assistant manager, and again when I took up my first managerial post at a small branch in Howden, Yorkshire. Every few years, I moved up the ladder and eventually became manager at one of the two main branches in Leeds. Our three children spent their childhood moving around, making new friends at new schools. It became normal for them and they have made lives for themselves in different parts of the world, although we have always remained a close family.

My wife had been born by the sea and wanted to return there, so we bought a flat in Exmouth. When I retired in 1983, we bought a house there and enjoyed life in Devon until I began to have health problems. It was hard for Bried to take care of me, so we moved to Horsham to be close to our daughter, Jacqueline. When my wife died two years ago, I was alone. Although people came to the house to provide help and support, I was susceptible to falls, so moved to Skylark House last year and the staff take good care of me.

In September, I celebrated my 100th birthday with family and friends. I have six grandchildren and an ever-increasing number of great-grandchildren, so we had a fine day. I received a card from the King and Queen, as well as a papal blessing from Pope Francis, arranged by Arthur Roche, a British cardinal of the Catholic Church.

Eighty years after I learnt it, I still remember morse code. I recently met two schoolboys interested in hearing about my time with the Royal Navy and I showed them the morse code manual handed to me during the war. I was very grateful when they sent me a ‘thank you’ letter in morse code!

As a D-Day veteran, I was awarded the Legion d’Honour, France’s highest decoration, to mark the 70th anniversary of the Normandy landings. This year, I attended the Remembrance service in Horsham, as I have done for many years. I remember all the people I saw die on Juno beach. I can’t ever forget them. I gather there are not many of us who served in the war who are still alive, so I feel it’s my duty to attend Remembrance and wear my medals. I don’t know what others think about it, but for me, it’s important that we remember them and what they did.

INTERVIEW: Ben Morris

PHOTOS: Alan Wright/Weaving family