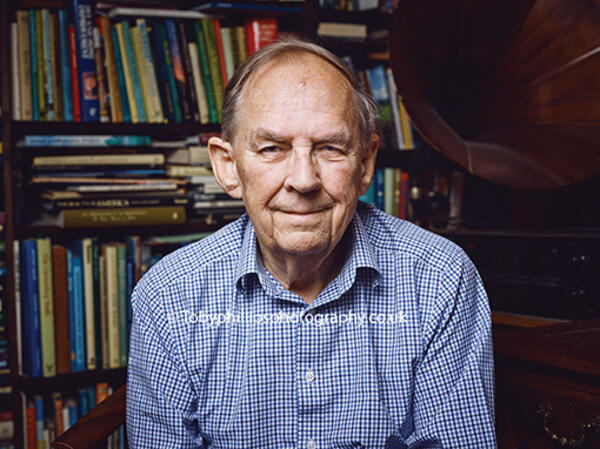

Sir Michael Checkland: My Years at the BBC

Published on 31st January 2017

I was born in Birmingham in 1936, the youngest of three children. My dad worked in a hardware store on Broad Street, so it was very much a working-class upbringing.

During the war, we had an Anderson shelter in the garden and my mother would carry me down every time there was an air raid. My brother and sister were evacuated and my dad was a fire warden, so it would just be the two of us huddled up.

I went to primary school, passed my 11-plus and progressed to King Edward VI Five Ways Grammar School. I was keen on sport and during lunch breaks we would catch the bus to watch cricket at Edgbaston.

My dad first took me to watch Birmingham City play football when I was seven. I remember being amazed by how far Frank Mitchell could head the ball, as they used heavy leather footballs back then. I became a life-long Birmingham supporter. I would support them at home games and watch Aston Villa in between. There were no divided loyalties - I went to see Birmingham win and Villa lose!

Although I won a scholarship to Birmingham University, my Head Master told me to apply to Oxford, as he felt I had a chance. My family were worried that it would be very different for me. However, Wadham College has long had a reputation for being relatively radical, in that it accepts a high proportion of grammar school students. It wasn't just public schoolboys, so it was easier to assimilate there than it might have been at other Oxford colleges.

Before Oxford, I committed to National Service in the RAF. I’m glad I did so, as it broadened my experience of life and introduced me to different people before I entered the protected world of Oxford. I studied Modern History and was captain of the Wadham College football team and also played for Oxford Pegasus.

The consensus was, if you had a History degree, you either joined the civil service, became a teacher, or went to work for the BBC. I ignored all of these options, instead gaining a professional qualification, as well as an academic one. I took accountancy exams and became a graduate trainee at Parkinson Cowan, which made gas cookers. I moved to Thorn Electronics Ltd in 1962, but wasn't getting much job satisfaction.

In 1964, I saw an advert for the BBC, which was launching a second channel, BBC2. They were employing about 2,000 people and I was part of that intake, as an accountant. The BBC wasn’t used to people with academic and professional qualifications, so it wasn't a very difficult interview for me!

I moved to Horsham at that time and would commute to London. Those early years were exciting as in 1966 we introduced colour. Everybody was suddenly interested in snooker, as it was a good show for colour television.

I held various positions within finance at the BBC for 10 years. I was involved in the costings side of programming, which provided me with an insight into how they were made. The next stage of my career came about when I was asked to manage Planning and Resources at BBC Television. This was a dramatic change of direction, as I had been Chief Accountant and suddenly I was involved in allocating studios and resources. My job was enabling programmes to be made, rather than choosing which programmes were made.

The work was varied, as the BBC also provided outside broadcasts. One such broadcast was the 1974 Eurovision Song Contest in Brighton, where ABBA won with Waterloo. That was a difficult event to organise due to the significant risk posed by the IRA. Security was very high and we even discussed if we should cover the event at all. But it all worked out and ABBA absolutely deserved to win.

In 1982, I was appointed Director of Resources at BBC Television. One of my jobs was to find the resources for a new soap called EastEnders. We bought an old studio at Elstree which was adapted to become Albert Square. My role also enabled me to attend major sporting events, including the Olympic Games and FIFA World Cup. During Italia ’90, I was driving through Turin with Bobby Charlton, who was working for the BBC. Everybody was waving to us but also getting out of our way, because it was Bobby Charlton of course!

I was once asked by Huw Wheldon, then Managing Director of BBC TV, if I had considered doing anything beyond finance. He said: ‘You're interested in sport, so why not try working on Match of the Day?’ I rejected the idea and occasionally wonder what would have happened if I had gone down that route.

I became Deputy Director-General in 1985. Soon after, Alasdair Milne left his post as Director-General. The Birmingham Mail ran an article suggesting I was a frontrunner for the job, although at the time I was considered an outsider, with David Dimbleby and Michael Grade amongst the favourites. However, during my interview, I spoke for 20 minutes and at the end everyone was still listening. I was appointed BBC Director-General in February 1987.

I outlined several key objectives. BBC Journalism had experienced a rough time and needed strengthening, so my intention was to bring news and current affairs throughout the BBC together, to create a journalistic hub. It was my view that the BBC had become too London-focused, and also needed to exploit commercial opportunities around the world. I had previously been Chairman at BBC Enterprises, the commercial arm, so I could see the potential. This has since evolved into BBC Worldwide, which makes an awful lot of money that can be invested back into programming.

During six years as Director-General, I feel I achieved my aims. The BBC was under substantial threat from Margaret Thatcher's government at the time. She didn’t support the licence fee and several members of her government were hostile towards us. They believed we shouldn’t be making popular shows and that the BBC’s output should be more highbrow. I believe - and most of my colleagues agreed – that the BBC needed a popular base, with comedy, sports and entertainment shows. It should also incorporate serious programming, focusing on the arts and current affairs.

I did have dinner at Downing Street and lunch at Chequers whilst I was Director-General. Every Wednesday, I would also have a political lunch with a member of the Cabinet or the Opposition, so I came to know most key people in Parliament.

My nickname was ‘Chequebook Checkland’ which was coined by a journalist, although nobody ever used it to my face. Journalists used it because I had a financial background, whereas previous Director-Generals had come from the editorial side. The reason I was selected for the job was that - at the time - the issues with the government and the survival of the BBC was more about resources and financing than it was programming. I was perceived as someone who was good with money and the BBC survived that hostility because we proved we were trying to run the place efficiently.

I presented Terry Wogan with a 50th birthday cake during filming for Wogan. It was a nice gesture that acknowledged the good work he was doing. We would host a light entertainment party every year where I would meet many stars, but Terry became a friend. We went to international rugby matches together in Ireland and Paris, as we were both fans. The obituaries were all true – he was genuinely a very nice chap.

Once a year, I did appear on a BBC series called See for Yourself. I sat alongside Marmaduke James Hussey, Chairman of the BBC Board of Governors, and we were asked questions by the public, with presenters including Sue Lawley mediating. One person asked ‘Why do you always employ stick insects as presenters?” I looked puzzled, but she was referring to the slim presenters. Someone asked ‘Why do Irishman run the BBC?’ He was referring to Wogan and Political Correspondent John Cole. A show like See for Yourself was a high-risk idea and other Director-Generals have said that they wouldn't have done it. But I knew my job well and was comfortable to face questions.

I also became Vice-President of the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), an alliance of public service media organisations. I helpedensure that the BBC was involved in negotiations to keep major sporting events, including World Championship Athletics, Winter and Summer Olympics and the FIFA World Cup. The BBC has managed to maintain those deals.

After an initial five-year appointment, I was offered a one-year extension, before my Deputy, John Birt, took over. The BBC made some big shows during those years – Only Fools and Horses, Blackadder, The Singing Detective – but key to my spell was that we managed to fend off the government’s criticism. My biggest success was that we survived the onslaught.

People have asked me about Jimmy Savile. Honestly, I don't know why we didn't know (about what he was doing). But then the prison service didn't know, the NHS didn't know; none of us realised what was going on. There was an enquiry and I was called to speak, but all I could say was that I didn't know anything. People look incredulous when you say that, but it's true. Of course, I regret it. It’s terrible that we didn’t see what was happening. It’s terrible that the rest of society didn’t see.

Even after retirement, I was involved in broadcasting for many years. I became a trustee of (international news agency) Reuters and served on the jury of The Peabody Award for five years. I also sat on the board of the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA). It was our role to regulate ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5. There were all sorts of issues relating to advertising, watersheds, decency, and whether ITV News at Ten could move back to 10:30pm.

As a Brummie, I became Chairman of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, when Simon Rattle was Musical Director. I was involved with the appointment of his successor, Sakari Oramo, who is now Conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Locally, I was chairman of Brighton Festival and during that time was involved in the redevelopment of Brighton Dome, which is one of the things I am most proud of. I was also Chairman of Horsham Fanfare, which started in 1995 and staged the type of event that the town had never seen before. We opened-up the park for Jools Holland’s Rhythm & Blues Orchestra and The Bootleg Beatles. The aim of Fanfare was to involve the local arts community, but also to widen the cultural experience of residents.

I wouldn't do the job unless it was supported by Horsham District Council. Chief Executive Martin Pearson gave us a £20,000 grant on the understanding that the fanfare delivered a district-wide festival. We staged Macbeth at Bramber Castle, opera at Parham House and The Capitol, and Fanfare opened with the Christ's Hospital School Band. Numerous local art, theatre and music groups were involved. The Fanfare was only possible through the council’s support, the hard work of the committee and particularly the staff at The Capitol.

I did that for five years before passing on the reins and was very sad when it fell apart. I don't know what happened, but I suspect that once Martin Pearson left the council, it became difficult to obtain the grant. The reason the current Horsham Festival focuses on local events is because it doesn't enjoy the support we had from the council and The Capitol. In my view, you need both to drive it forward.

For 10 years from 1992, I was Director of the National Youth Music Theatre (NYMT). Several young people, including Jude Law and Sheridan Smith, have gone on to big things. I was also Chairman of the National Children’s Home, now Action for Children. It was a Methodist-based charity and I've long been a member of London Road Methodist Church. In fact, in 1997, I became Vice- President of the Methodist Church. One other important role was as Chairman of Horsham YMCA, at a time when The Y Centre was being built.

The final strand of my post-BBC life is in higher education. I was appointed Governor at Birkbeck College, London, which offers evening classes that appeal to mature students. This role was important to me as I believe in second chance education. I was also Governor at Westminster College, Oxford and Chairman of Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). I was appointment by a Labour government to help raise quality across the board and create new medical schools, including the Brighton and Sussex Medical School.

I have enjoyed the multi-faceted range of jobs since retirement as they've all reflected my interests. However, it was my years at the BBC that allowed me to do these other things in later life.

Sue and I married in 1987, both for the second time. We moved to Maplehurst and have been there for 30 years. Sue still takes part in the annual village scarecrow competition. Between us, we have six sons and daughters, some close by and others in such countries as Australia and Vietnam. This has meant that we travel a lot. The one place I would still love to visit is Easter Island. I was due to be on holiday in Chile this month. However, just before Christmas, I suffered a heart attack.

We had been to Christ’s Hospital to watch Les Miserable and I drove there, spoke to people and apparently enjoyed the show. But I don’t remember any of that. The next day, I had a heart attack and needed a triple heart bypass. After five weeks in hospital, I am now recovering at home. I consider myself fortunate that I wasn’t out in the Atacama Desert when I had the heart attack!

As to my thoughts on the BBC today, I’m delighted that the licence fee has been retained. I'm delighted that nobody has attempted to strip the range of programming, and I'm pleased that the BBC Trust has gone, as I never liked the old structure. In recent years, the BBC has taken to new technology in a positive way. You only need visit the website to see how strong it is. That can be dangerous, as when the BBC becomes too dominant, people feel threatened by it.

The current Director-General Tony Hall, who was Director of News and Current Affairs in my day, has done well. He moved BBC3 online, which was right because of its young audience. There will always be criticisms of individual programmes, but I don't agree with people who say there's nothing on television these days. If you look around, there’s plenty.

I am a stoutly proud BBC man. You can travel all around the world and everywhere you go, the BBC is still the hallmark of quality broadcasting.